Activation of Human Natural Killer Cells by Graphene Oxide-Templated Antibody Nanoclusters (Loftus et al., 2018)1

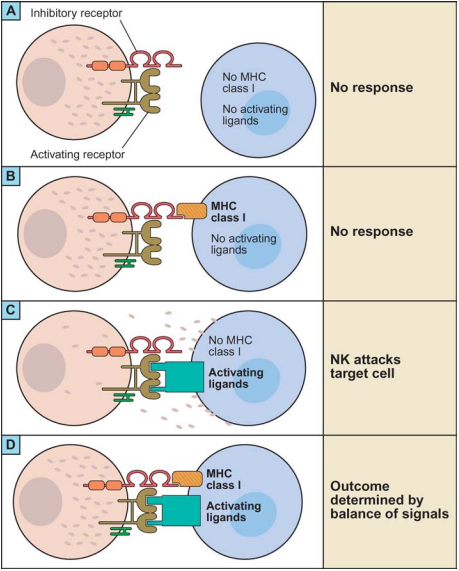

With a name like “Natural Killer Cells”, we can assume NK cells are the cool kids of the immune system. They are a type of lymphocyte closely related to T-cells, forming part of the innate immune system. NK cells are able to kill virus-infected or tumour cells without the priming by antigen-presenting cells needed by the killer T-cells.2 Activation of NK cells seems to be quite complex, depending on the balance of activation by multiple families of ligands and inhibition by the MHC-1 receptor which indicates “self-ness” in the body (figure 1).

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Activation of NK Cells, reproduced from Lanier, 20053 |

Activated NK cells form an immune synapse with the target cell, allowing the NK cell to empty its lytic granules into the target cells and trigger cell death.4 The lytic immune synapse is closely related to the immune synapse formed between a T-cell and an antigen-presenting cell in T-cell activation. Adhesion between the two cells is mediated by LFA-1 and other integrin proteins in both cases, and as we’ll see this paper is built on the similarity of the two assemblies.

What’s this team trying to do then?

T-cell activation is believed to depend on the interaction of nanoscale clusters of receptors (e.g. of TCR) on the T-cell surface with nanoscale clusters of ligands (e.g. MHC) on the antigen presenting cell. This work is about applying that insight to the closely related lytic immune synapse of the NK cells, and hence to design nanoparticles which efficiently activate NK cells.

Particle Design

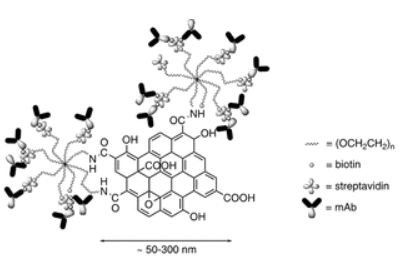

The particles they designed consist of a nanoscale graphene oxide (NGO) core, approximately 150nm in diameter (figure 2), linked to PEG stars. The 150nm size is chosen to match approximately the size of clusters of surface receptors observed on the NK cell surface, and TCR clusters in activated T-cells. The PEG functions to stabilise the NGO colloid in physiological fluid (it crashes out if not sufficiently pegylated), and prevents opsonisation.

|

|---|

| Figure 2: Nanocluster design, reproduced from Loftus et al., 20181 |

The free end of the PEG stars is then biotinylated and coated in excess streptavidin (excess to prevent crosslinking), allowing flexible attachment of biotinylated antibodies. Fluorescence-labelled antibodies allowed the authors to count the number of antibodies on each side of the NGO – 60-70 per side for the 150nm clusters. Smaller clusters could also be separated (down to 72nm) by centrifugation, as the larger clusters pellet first.

Binding to NK Cells

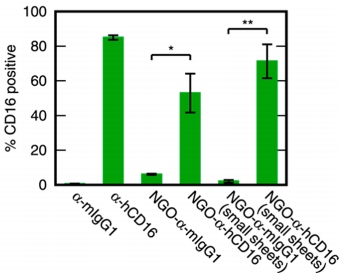

The antibodies used to bind NK cells are α-hCD16, which binds the CD16 receptor found on the NK cell surface and known to activate those cells. Fluorescence labelling of the antibodies allowed binding to NK cells to be assessed by flow cytometry, and indeed they were found to label ~50% of NK cells in donor peripheral blood (figure 3). Note that free α-hCD16 binds labels around 80% of cells here – that’s relevant in the next section.

|

|---|

| Figure 3: Binding of NK Cells, reproduced from Loftus et al., 20181 |

Activation of NK Cells

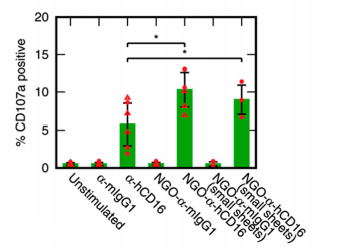

The assay for NK cell activation they used is very neat. CD107a is a glycoprotein component of the membrane of lytic granules. When the NK cells are activated the vesicles fuse to the cell membrane, releasing their contents (perforin, etc.) into the target cell. Consequently, the CD107a content of the cell membrane, which is measurable by flow cytometry, indicates which cells have or haven’t been activated.

Happily, they found the nanoparticles do indeed activate NK cells more effectively than does dissolved α-hCD16 (figure 4): around 10% of cells were activated, rather than 5% for the free antibodies. Interestingly, the small and large nanoparticles had statistically indistinguishable effect, suggesting a relatively small threshold size beyond which further clustering does not increase efficiency.

|

|---|

| Figure 4: NK Cell Activation, reproduced from Loftus et al., 20181 |

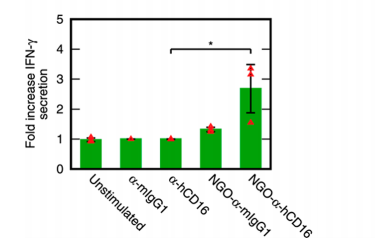

NK cells are also known to secrete cytokines such as IFN-γ, which enhances T-cell and macrophage response. The results here are very clear-cut – the nanoparticles increase cytokine secretion 2.7-fold over background, where un-templated free α-hCD16 has no impact (figure 5).

|

|---|

| Figure 5: Stimulation of Cytokine Secretion, reproduced from Loftus et al., 20181 |

What’s next?

This is very interesting work, both in how the nanoparticles were designed and the methods used to characterise their impact on NK cells. So, a lot of further questions arise. The most immediate, to me, is whether these particles can effectively induce NK cells to lyse a cell to which they’re attached. That would allow them to be used to guide the immune system to attack cells which are currently unaffected, such as self-identifying tumour cells. The biotin/streptavidin system used to generate the NPs is sufficiently modular that it hopefully lends itself to attachment to a cell surface. The other area I would love to understand better is the relatively low NK cell degranulation, of around 10%. The authors note that only 10-20% of NK cells degranulate in a physiological immune reaction too – I wonder where these particles could be used to separate the “activatable” and “non-activatable” sub-populations and allow further exploration of the differences between the two.

References

- Loftus, C., Saeed, M., Davis, D. M. & Dunlop, I. E. Activation of Human Natural Killer Cells by Graphene Oxide-Templated Antibody Nanoclusters. Nano Lett. 18, 3282–3289 (2018).

- Eissmann, Philipp. Natural Killer Cells. https://www.immunology.org/public-information/bitesized-immunology/cells/natural-killer-cells.

- Lanier, L. L. Nk Cell Recognition. Annual Review of Immunology 23, 225–274 (2005).

- Orange, J. S. Formation and function of the lytic NK-cell immunological synapse. Nature Reviews Immunology 8, 713–725 (2008).