Auxetic Cardiac Patches with Tunable Mechanical and Conductive Properties toward Treating Myocardial Infarction (Kapnisi et al., 2018)1

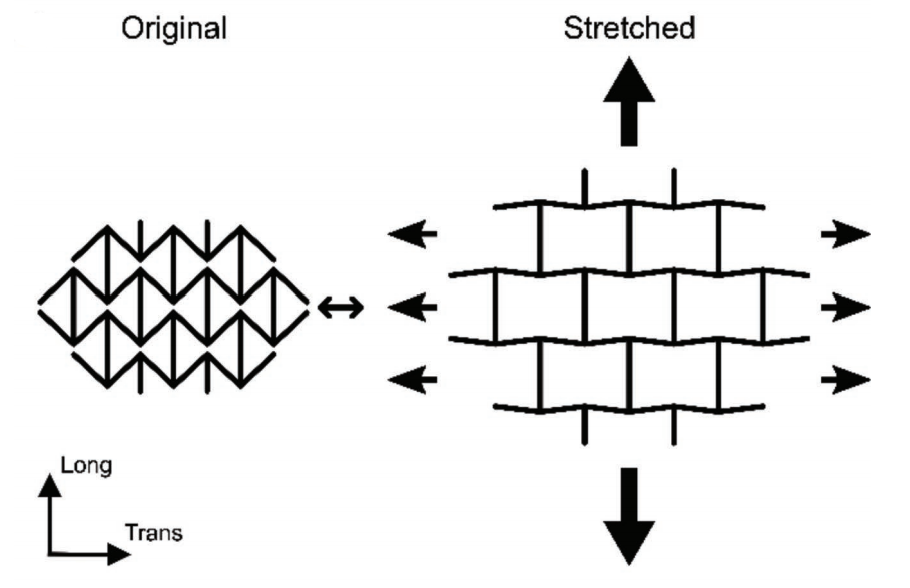

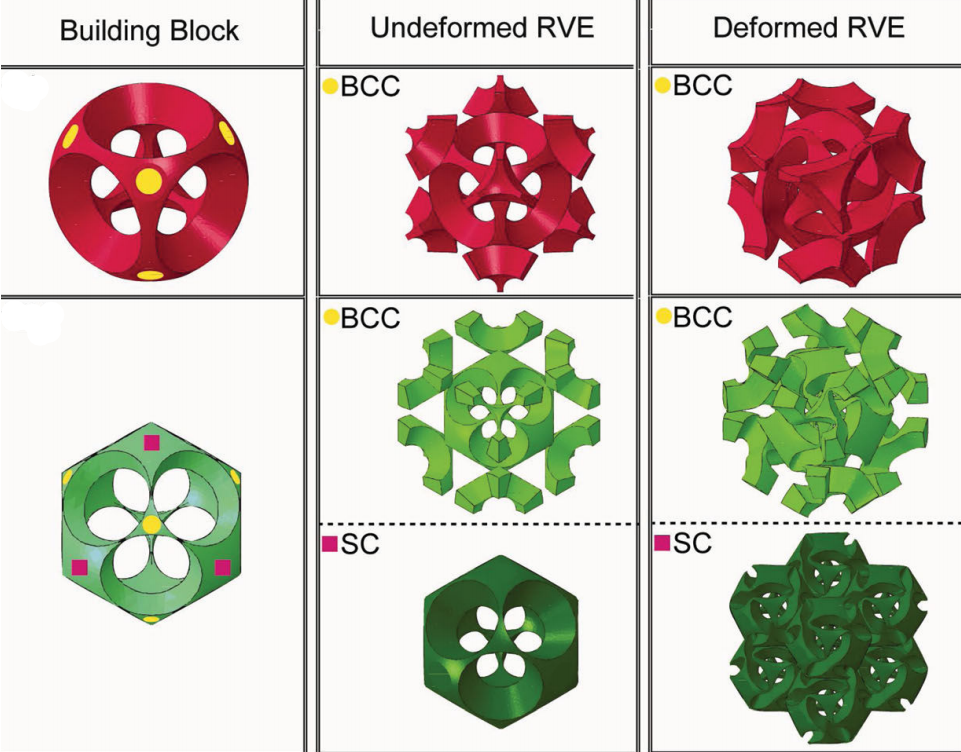

Picture a piece of rubber being stretched: as it gets longer, it also gets thinner and narrower. The extent to which a material gets thinner in the perpendicular directions as it stretches is known as the Poisson ratio. Auxetics are a class of material with a negative Poisson ratio – as they stretch, they also get wider! They do this because they have particular microstructural geometry which flexes as the material stretches. A range of auxetic geometries have been produced, including the bow tie patterns used in this work (Figure 1a) and Bucklicrystals2 (1b).

|

|

|---|---|

| Figure 1: a) Bow tie auxetic pattern, reproduced from Kapnisi et al., 20181 | b) Bucklicrystals, reproduced from Babee et al., 20132 |

Why are they interesting for cardiac applications?

Cardiac muscle has two unusual mechanical properties:

1) The Young’s modulus of the heart varies substantially (between 0.02 and 0.50 MPa) between systole and diastole

2) The heart’s stiffness is asymmetric – it is 2-4 times stiffer circumferentially than longitudinally

In an auxetic material the stiffness in each direction and the anisotropy of stiffness can both be tuned by varying the dimensions of the patterns. Theoretical models have been developed to precisely guide design.3 So, we might be able to design materials which match the stiffness of the heart precisely, and hence heart patches which accommodate the motion of beating.

What was the substrate?

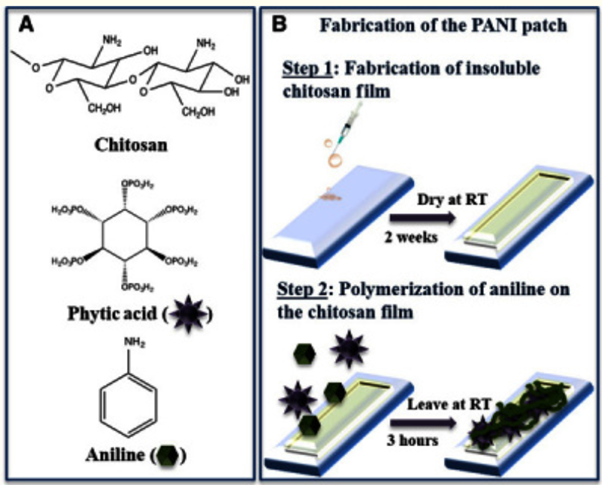

The group had already described4 conducting cardiac patches formed from chitosan films linked (ionically) through phytic acid to the conducting polymer polyaniline (formed in situ by persulfate oxidation of aniline) (figure 2). Auxetic patterns were then ablated onto the surface with an excimer (UV) laser.

|

|---|

| Figure 2: Patch substrate, reproduced from Mawad et al., 20164 |

Did it work?

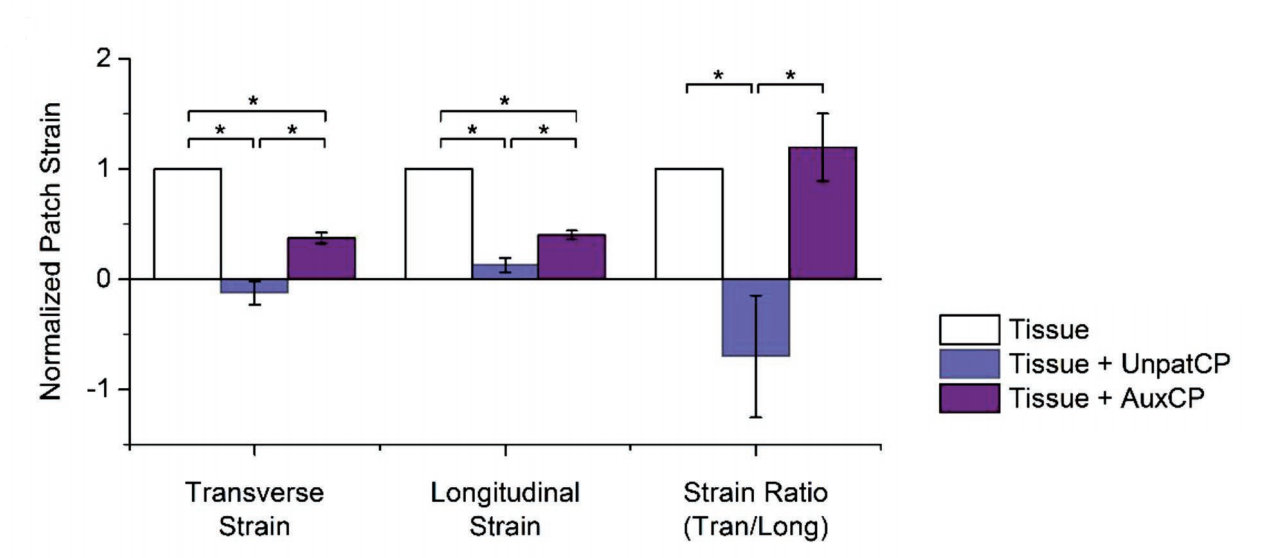

The mechanical impact of the patches was investigated ex vivo, by gripping dissected sections of the left ventricle with the patch applied and stretching cyclically. The auxetic patches do stretch more than the un-patterned version (figure 3), but still much less so than unpatched tissue. Pleasingly, the axial/longitudinal ratio of stretching is the same with the auxetic patch as for unpatched tissue. So, the material is perhaps a bit too stiff, but the anisotropy designed in appears to be appropriate.

|

|---|

| Figure 3: Ex Vivo Mechanical Strain, reproduced from Kapnisi et al., 20181 |

References

- Kapnisi, M. et al. Auxetic Cardiac Patches with Tunable Mechanical and Conductive Properties toward Treating Myocardial Infarction. Advanced Functional Materials 28, 1800618 (2018).

- Babaee, S. et al. 3D Soft Metamaterials with Negative Poisson’s Ratio. Adv. Mater. 25, 5044–5049 (2013).

- Masters, I. G. & Evans, K. E. Models for the elastic deformation of honeycombs. Composite Structures 35, 403–422 (1996).

- Mawad, D. et al. A conducting polymer with enhanced electronic stability applied in cardiac models. Sci Adv 2, (2016).