Direct Conversion of Adult Human Fibroblasts into Functional Endothelial Cells Using Defined Factors (Han et al., 2021)1

This paper stood out for its combativeness – they state outright that a group of published papers which claim to have achieved fibroblast to endothelial transition in cells did not. They go on to show how it should have been done, and in doing so explain a lot of how to comprehensively characterise cell phenotype.

Direct Transdifferentiation

Direct transdifferentiation is the conversion of one fully differentiated cell phenotype into another, without passing through an intermediate de-differentiated type (i.e., without conversion to a stem cell intermediate). The direct conversion of human fibroblasts to a number of different cell type targets has been demonstrated2, and typically proceeds by induction of master regulator transcription factors.

Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transitions (EMTs)

Epithelial to mesenchymal transitions are processes in which polarised epithelial cells transition to a mesenchymal phenotype.3 The basement membrane beneath the transitioned cells degrades, and the mesenchymal cells are able to detach and become mobile. EMTs occur naturally in three sets of circumstance:

1) During implantation and development of an embryo.

2) During inflammation and fibrosis. This is associated with TGF-β1 signalling.

3) In tumours and carcinomas. The mobility of the mesenchymal cells is associated with metastasis in cancers.

The specific subset of the endothelial-mesenchymal transition is known, but less well studied. It does seem to have very similar biochemistry though.

“Endothelialness”

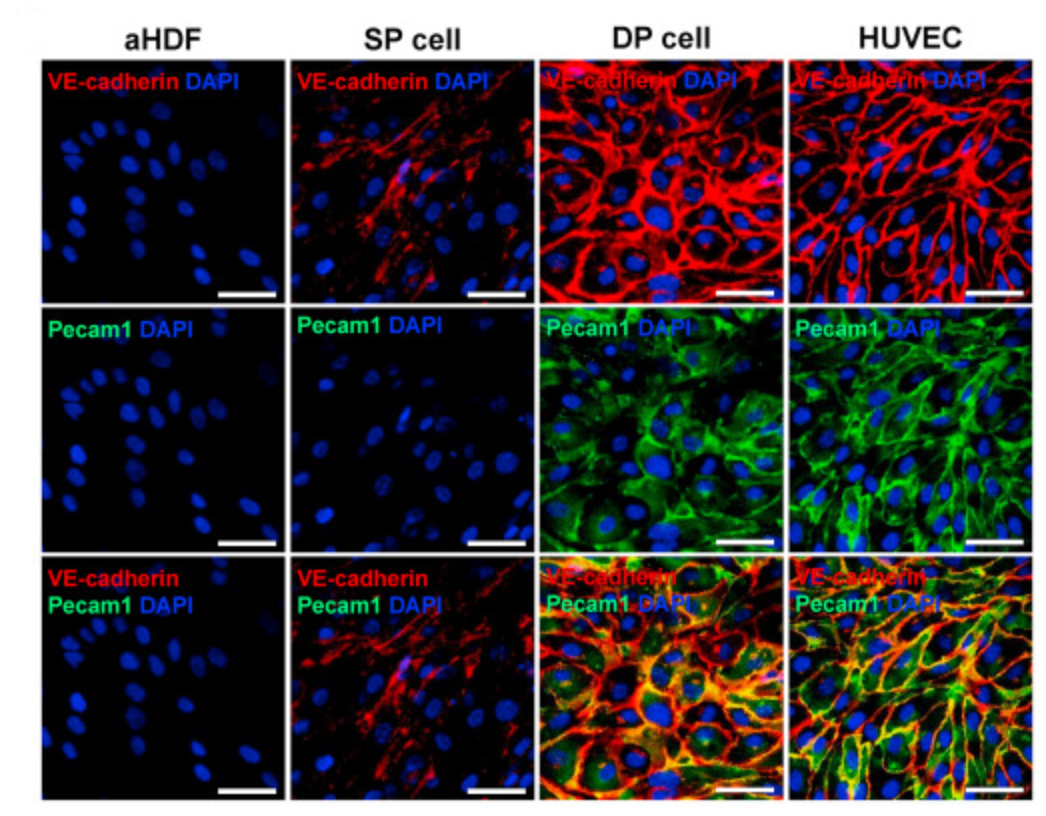

If we’re trying to convert fibroblasts to epithelial cells, we’ll need a way to screen for the endothelial phenotype efficiently. Initially, they do this by immunofluorescence labelling of VE-Cadherin (the cells are stained with anti-VE-cadherin antibodies, which are then stained with secondary antibodies which recognise the primary antibodies and are conjugated to a fluorophore). However, RNA sequencing of the VE-cadherin positive cells which they initially induced showed an intermediate expression profile which is in fact closer to dermal fibroblasts than to endothelial cells. These “single positive” cells lack the “cobblestone” appearance of endothelial cells, and do not express Pecam1, usually a stable marker of endothelial cells.

So, Han et al. used flow cytometry to isolate a sub-population of cells which express both VE-Cadherin and Pecam1, which they term “double positive” cells. The double positive cells have morphology which matches the target endothelial cells, and similar distributions of VE-Cadherin and Pecam1 (figure 1).

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Comparison of Fibroblast, Single Positive, Double Positive, and Endothelial Cell Stains, reproduced from Han et al. (2021)1 |

Achieving Complete Conversion

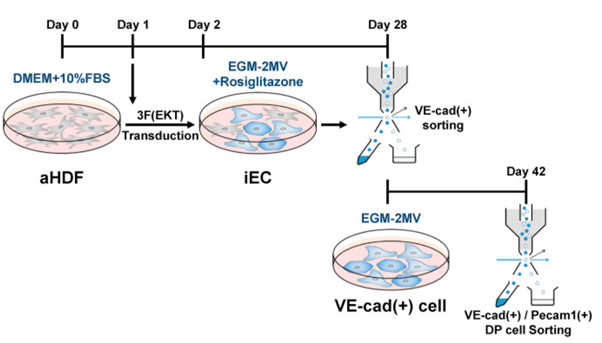

Conversion of fibroblasts to the fully endothelial double-positive cells is accomplished with a two-stage procedure (figure 2):

a) Transduction with three transcription factors (ERJ1, KLF2, TAL1). After 1 day, Rosiglitazone, a chemical inhibitor of EMT, is added.

b) After 28 days, the cells are sorted for VE-Cadherin expression. It was found that Pecam1 expression was much higher with this enrichment step than in cells which are simply cultured for the full six weeks without intermediate sorting.

|

|---|

| Figure 2: Procedure for Production of Double-Positive induced Endothelial Cells (iECs), reproduced from Han et al. (2021)1 |

I found this procedure very interesting for its addition of Rosiglitazone. Presumably the natural possibility of EMT means a mesenchymal-like intermediate cell state is more stable than an intermediate state might otherwise be, and suppressing that transition makes this direct conversion more tractable.

Confirmation of Phenotype

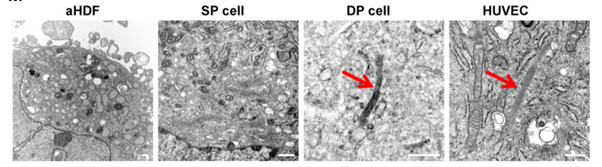

The phenotype and functionality of the induced endothelial cells was assessed quite comprehensively – probably necessary, given their main claim is that prior attempts at inducing this transition didn’t properly characterise the end state! Key confirmations were:

1) Cell morphology

2) RNA transcription profiles which match human endothelial cells much more closely than the single positive cells did

3) Epigenetic profiling of Pecam1 and VE-Cadherin

4) The ability of the iECs to form tubes in Matrigel (figure 3)

|

|---|

| Figure 3: Matrigel Tube Formation in Double Positive Cells, reproduced from Han et al. (2021)1 |

Assessing the Existing Literature

Finally, the comparison to prior reports of fibroblast to endothelial conversion is very interesting. There seem to be two possible sources of disagreement:

1) Some previous procedures used neonatal or amniotic fluid-derived cells as the starting point. These may be more plastic than the adult fibroblasts Han et al. used. This appears to be the case in particular for Ginsberg et al.4, who reported their procedure did not work for adult fibroblasts.

2) Some prior reports may not have sufficiently characterised the iEC products. For example, they may not have characterised full RNA expression profiles, and therefore may not have detected that the induced cells failed to express important EC markers such as NOS3.

References

- Han, J.-K. et al. Direct Conversion of Adult Human Fibroblasts into Functional Endothelial Cells Using Defined Factors. Biomaterials 120781 (2021) doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120781.

- Vierbuchen, T. et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature 463, 1035–1041 (2010).

- Kalluri, R. & Weinberg, R. A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 119, 1420–1428 (2009).

- Ginsberg, M. et al. Efficient Direct Reprogramming of Mature Amniotic Cells into Endothelial Cells by ETS Factors and TGFβ Suppression. Cell 151, 559–575 (2012).