Hydroxyapatite nano and microparticles: Correlation of particle properties with cytotoxicity and biostability (Motskin et al., 2009)1

Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles

Hydroxyapatite (HA) is the primary mineral component of bone. As you can imagine, that means its often used in synthetic scaffolds for bone graft. However, this paper describes nanoparticles, which are certainly not a scaffold. That’s because HA nanoparticles have been explored quite extensively as delivery vehicles for drugs and biological factors. They’re attractive because they readily adsorb proteins, they degrade in vivo, and they’re very easy to tailor both chemically and physically. However, there are significant safety concerns associated with their use. Although large HA deposits degrade slowly and safely in the body, nanoparticles have an enormously larger surface-area-to-volume ratio, and hence dissolve far faster. This could lead to rapid increases in Calcium ion concentration, with consequences for cell health and possible re-deposition of minerals as seen in atherosclerotic plaque.

Synthesis of HA Nanoparticles and Microparticles

The safety of nanoparticles (NPs) in general is complicated to explore because they are heavily influenced by physical properties (e.g. particle size or aspect ratio). So, Mostkin et al. compared several “HA nanoparticle” preparations:

- A gel of nanoparticles formed by sonicating Calcium Chloride with Sodium Orthophosphate

- A colloid of nanoparticles formed by adsorbing citrate onto the gel

- Microscale spheres of densely-packed nanoparticles by spray-drying the gel

- Microscale “blobs” of densely-packed nanoparticles by spray-drying the colloid

- Commercially available nanoparticles

Characterising the Particles

The nanoparticles were characterised as HA by powder XRD (for structure) and atomic emission spectroscopy (for stoichiometry). The aspect ratio and dimensions of the nanoparticles were assessed from the X-ray diffraction data via the Scherrer equation, confirmed by manual measurement of a representative sample in TEM images.

Microparticles were porous, and the degree of porosity was measured by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller method – essentially the total accessible surface area of particles is measured from the amount of gas which can adsorb to the surface. Microparticle dimensions were again assessed from powder X-ray data, and confirmed by microscopy (this time SEM).

Cytotoxicity

As we said at the start, HA is often used to coat dental or orthopaedic implants, due to its similarity to natural bone and ability to stimulate growth of new bone in healing. However, mechanical wear of those surfaces produces debris particles which have been implicated in chronic inflammation and necrosis by stimulating monocytes/macrophages.2 So, this work uses macrophages as a model for the effect of HA nanoparticles on cell viability.

Cell viability was assessed by an MTT assay (for metabolic activity) and an LDH assay (which detects leakage of lactate dehydrogenase into the culture medium when the cell membrane is damaged). In both cases, greater toxicity at lower dose levels was seen for the gel nanoparticles (figure 1). The colloid nanoparticles were less toxic than the gels, but still worse than either of the micro-scale aggregates.

|

|---|

| Figure 1: Cytotoxicity of HA Preparations, reproduced from Motskin et al., 20091 |

Uptake by Macrophages

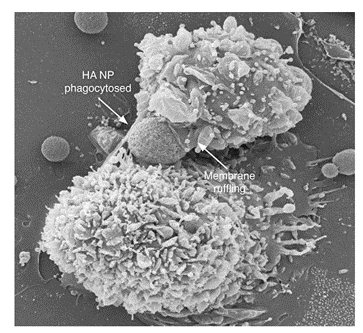

The nicest part of this paper is the imaging studies done to elucidate the fate of HA absorbed by macrophages. The SEM image in figure 2 is quite extraordinary – a macrophage caught in the process of engulfing a nanoparticle!

|

|---|

| Figure 2: Macrophage engulfing an HA nanoparticle, reproduced from Motskin et al., 20091 |

Key findings of the imaging study were:

1) NPs are absorbed actively (no absorption is seen at 4°C)

2) The engulfed particles are progressively broken down and dissolved in the acidic environment of the lysosome

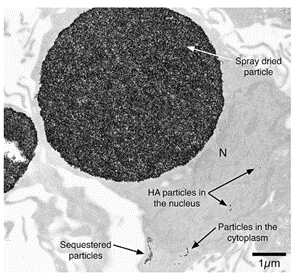

3) Some nanoparticles can escape the lysosome and enter the cytoplasm or even the nucleus (figure 3). This may be due to the raised Ca2+ concentration as the HA dissolves, as intracellular calcium is known to assist endosomal escape of transfection agents.3

|

|---|

| Figure 3: Escape of Nanoparticles into the Cytoplasm and Nucleus, reproduced from Motskin et al., 20091 |

Summary

The key takeaway from this work, I think, is that toxicity of nanoparticles is highly variable depending on their physical characteristics. The higher toxicity of gel particles is probably a consequence of their less negative zeta potential (due to absence of adsorbed citrate) and rod shape, both of which increase the rate of cellular uptake.4 The strategy of spray-drying the nanoparticles to form microscale aggregates which release much more slowly in the cell is very interesting. I’d be very interested in whether it’s been applied elsewhere since, but this is a very highly cited paper so there’s a lot to look through and I haven’t found a good example yet!

References

- Motskin, M. et al. Hydroxyapatite nano and microparticles: Correlation of particle properties with cytotoxicity and biostability. Biomaterials 30, 3307–3317 (2009).

- Harada, Y. et al. Differential effects of different forms of hydroxyapatite and hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate particulates on human monocyte/macrophages in vitro. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research 31, 19–26 (1996).

- Zaitsev, S. et al. Histone H1-mediated transfection: role of calcium in the cellular uptake and intracellular fate of H1-DNA complexes. Acta Histochemica 104, 85–92 (2002).

- Gratton, S. E. A. et al. The effect of particle design on cellular internalization pathways. PNAS 105, 11613–11618 (2008).